Sudden understanding — individual and collective

This is part two of a three-part systemic exploration of fast-thinking and slow-thinking. Part two explores key ideas from these two approaches to thinking in greater detail and subtlety than when introduced through the popular binary model postulated by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (introduced in part one). Kahneman and Tversky’s schema is not the only well-thought-out model for thinking about thinking, but it is a handy inception point for a more nuanced stance and approach to the topic. It is also a good point of reference because of the influence and reach of their work and its acceptance in the professional, governmental, business, and academic environments.

Their postulated binary model or schema is a convenient stepping off point for a deeper and broader exploration of thinking as related to design inquiry, particularly systemic design inquiry. Specifically, it takes a careful look at the design of inquiry for action to be followed by action in complex, indeterminate environments.

As a continuation and expansion of this line of thinking as introduced in my previous Substack post — Thinking Amid Complexity (https://hnelson.substack.com/p/thinking-amid-complexity). The present focus is on a manifestation of fast-thinking I have called fast-thinking type B, an addition to Kahneman and Tversky’s binary model. This is the kind of thinking that has allowed humans from the beginning to survive and thrive in dangerous, indeterminate, complex environments. It is the type of fast-thinking that is sudden and transformative, expressed through creative insights, ah-ha moments, and design partis that slow-thinkers can’t, don’t, or won’t experience in their approaches to instrumental inquiry.

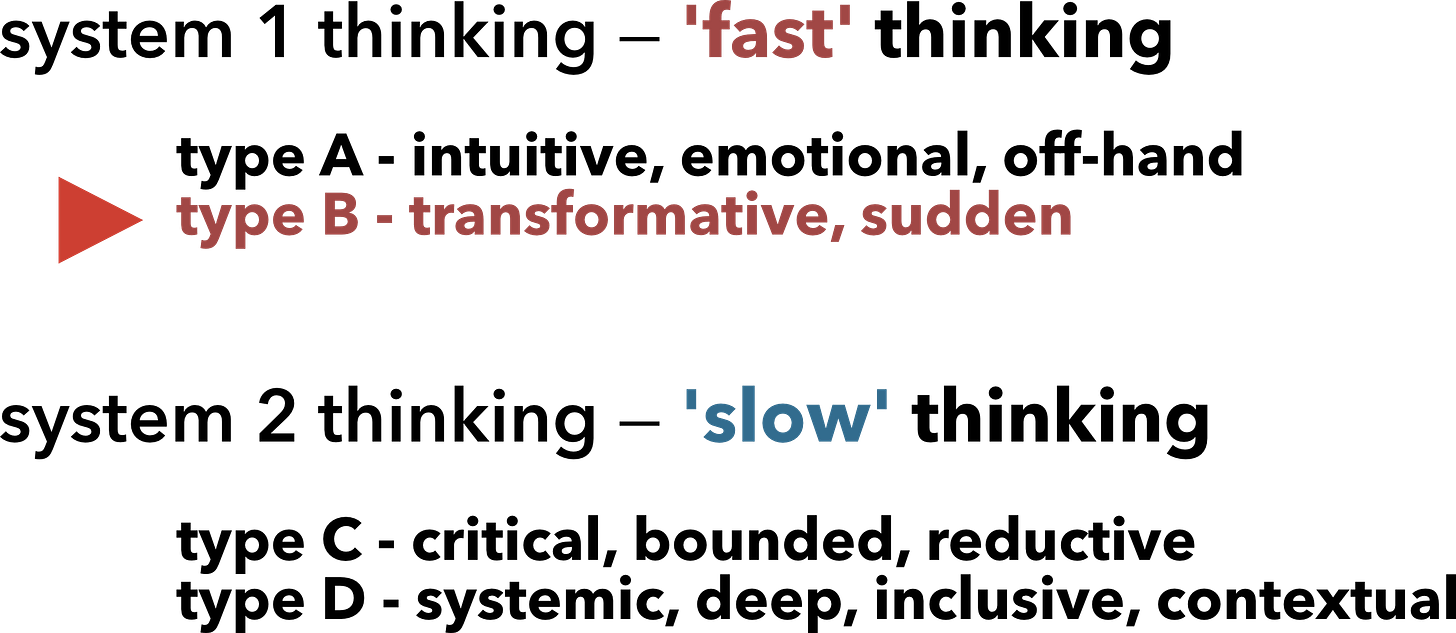

This point of departure is a more nuanced look at fast-thinking in the context of complex entanglements that are naturally occurring states in the modern world. Fast-thinking in this instance is posited as a compound of types A and B, relative to slow-thinking as a compound of types C and D, as shown below. In this follow-up account, I look more closely into fast-thinking type B primarily.

Sidebar — A third style of thinking is synthetic-thinking

A third style of thinking is synthetic-thinking. The resultant outcomes of synthetic-thinking are compounds, assemblies, compositions, emergent qualities, and emergent wholes. The outcomes are prudent and pragmatic means for working with complexity in a competent way.

Systemic-thinking — a form of synthetic-thinking — is an inclusive compound of fast and slow thinking and is a much better match for creating or changing complex entanglements than is the simple binary reduction of thinking into fast and slow alternatives. The reduction of the act of thinking into a simplified binary choice lacks opportunities for deep, inclusive, and diverse thinking.

The outcomes of synthetic thinking, such as conjunctions, assemblies, compositions, emergent qualities, and emergent wholes, are prudent and pragmatic means for thoughtfully and successfully dealing with the reality of working with complex entanglements, often misidentified as wicked problems.

Back to fast-thinking.

Creative-thinking is a type of fast-thinking with a dash of slowish-thinking thrown in. Creative-thinking makes sense of, gives meaning to, and shapes complexity, which is the reason creativity is so valuable to the human enterprise. Creative-thinking is necessary and essential to design and innovation.

Humans from the beginning survived and thrived in complex, dangerous environments because of fast thinking. Fast thinking is making sense and giving meaning to entangled, complex situations that are indeterminate when it comes to outcomes.

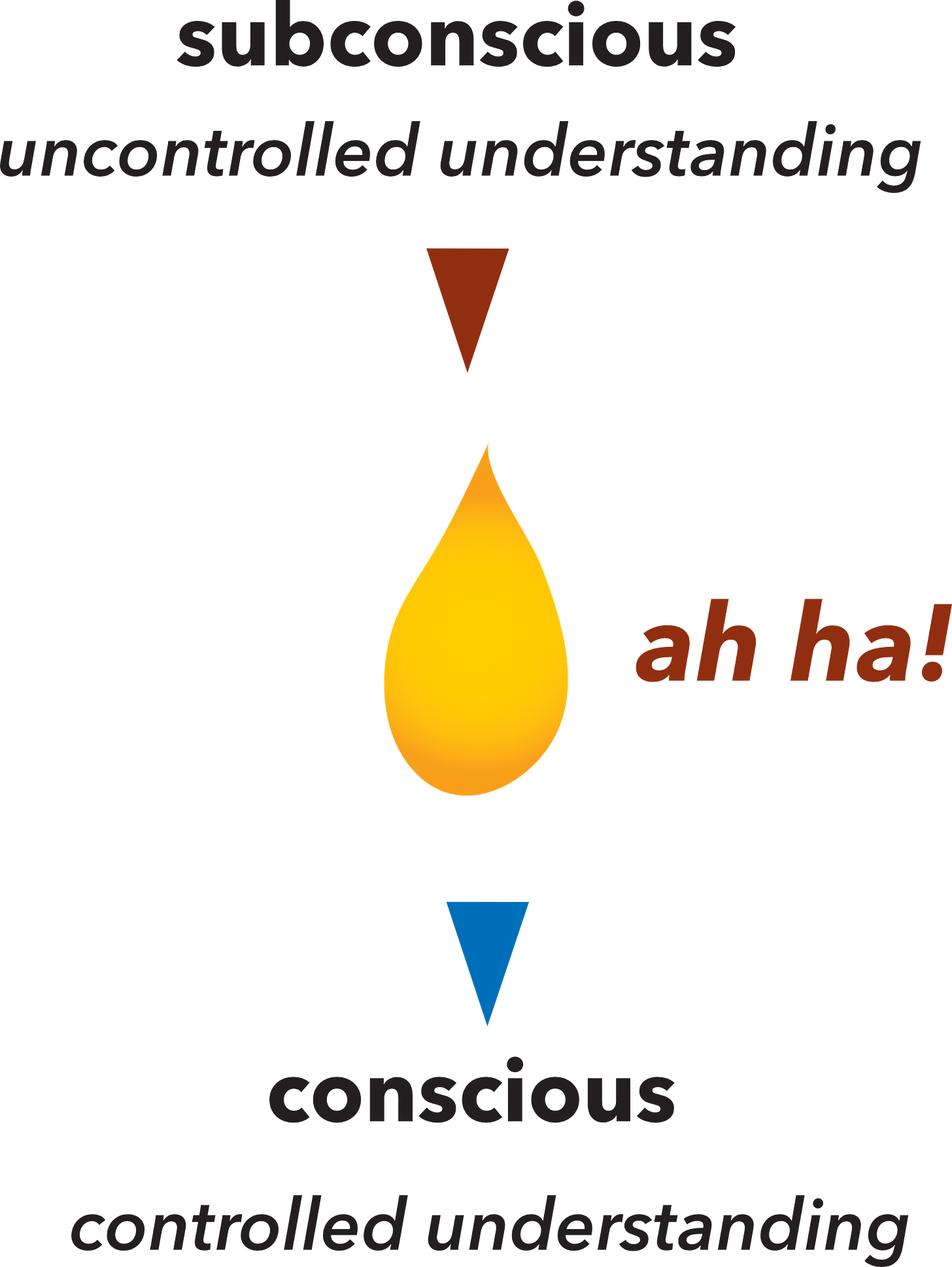

Fast-thinking by one approach can be seen as a compound process moving from intentional preparation, a kind of slow-thinking, to sudden breakthrough understanding; the consequence of fast-thinking.

Sudden understanding can be unprompted and without deliberate preparation. An analogy for the dynamics of fast-thinking can be seen in the behavior of a supersaturated chemical solution — a dramatically different kind of solution than the kind that comes from successful problem solving.

The chemistry example of a supersaturated solution is fairly common in science. You will notice that the solution crystallizes suddenly when a ‘seed’ particle is added to the supersaturated solution, moving it from a stable state to another ordered state:

In a social system, an analogue to ‘supersaturated solutions’ is created through free-form social interactions like conversations or open exchange dialogues. Ideas, observations, and questions can be added to an ongoing conversation or dialogue process, analogous to forming a social-saturated solution (not a problem-solving solution) that becomes more saturated with ideas as it progresses. This social-saturated solution can be enriched to a point of supersaturation. With the addition of a new idea or thought, the shared exchange will suddenly crystallize into an insight that elevates the indeterminate dialogue or conversation to greater understanding.

An example of a dialogue process was formulated by the MIT Dialogos Project (“the art of thinking together”) by William Isaacs and used to resolve conflict in businesses and governmental organizations (https://www.dialogos.com). It has proven to be very practical in real-world settings.

video

book

https://www.amazon.com/Dialogue-Thinking-Together-William-Isaacs/dp/0385479999

My colleagues and I adapted this type of dialogue process to creating social-saturated solutions at ISI (International Systems Institute) Asilomar gatherings with some success. This was an experiment that needed follow-through.

Changing your mind by changing lenses & filters

A simple initial strategy for facilitating fast-thinking is to choose, change, or modify the lenses and filters used to mediate external sense data with the internal cognitive activities.

Filters and lenses

Changing approach by changing perspectives

The next strategy is to choose the perspective or approach used in dealing with a complex, entangled situation, or even simpler, merely complex situations. For example, Harold Linstone (Decision Making for Technology Executives (https://us.artechhouse.com/Decision-Making-for-Technology-Executives-Using-Multiple-Perspectives-to-Improve-Performance-P1043.aspx )) developed and tested three basic perspectives (shown in red below) with great success. His work led others to develop other kinds of fundamental perspectives to be used in decision making, planning, managing, or designing. Lindstone combined or integrated the different insights unique to each of his perspectives to form input into an inclusive decision-making process.

Multiple perspectives for systems assessment

sharing perspectives on the ‘whole’

Disciplined and un-disciplined inquiry contrast the collaborative approach to inquiry with shared or multiperspective inquiry. Both are essential, but un-disciplined inquiry is not commonly used, and it needs to be.

collaborative vs shared perspectives

Integrating multiple perspectives and points of view

Orienting and organizing the various multiple perspectives can be accomplished using different approaches. Below is one example of associating perspectives with points of view.

Perspectives re points-of-view

Thinking-fast aided by reframing frames-of-reference

Frames-of-reference are dimensions of a cognitive framework that reveal additional insights beyond those gained through perspectives and points of view.

An example of reframing frames of reference

Sudden collective understanding

Collective inquiry leading to shared insights and sudden understandings is not a collaborative process. It is the dynamic of a social system that is more complex and systemic. Below is an example of a collective inquiry process.

collective inquiry for understanding and action

An individual’s understanding

The process of thinking-fast is given direction by the deliberate choice of lenses and filters for gathering sense data, for example. As a case in point, quantum listening can be thought of as choosing channels (filters) — states of listening — to allow in only certain spectrums of information while blocking out others. By ‘changing channels’ for listening, the range and nature of inputs are narrowed and filtered, decreasing the spectrum of complexity that can be considered.

quantum listening

Epiphanies, eureka effects, and ah-ha moments are common experiences of individuals when gaining sudden insights, unbidden and unexpected. Because they appear to be uncontrolled or uncontrollable, they are not typically part of any preparation for experience in professional practice. Including them in professional training or formal education programs is rare, but that needs to be changed.

Inquiry for prudent action followed by innovative action is the basis of systemic designing or, any type of designing. The challenge of gaining competence as a systemic designer is to accept that complexity is something to embrace and work with and not avoid. This includes sweeping in all forms of inquiry.

‘Score’ for combining fast (B) and slow (D) thinking in systemic designing

Scoring a dynamic system process is the same as scoring music or dance. The stages and phases in a design inquiry score represent different kinds of inquiry and different kinds of knowing, as well as knowledge from different kinds of thinking. The knowing that emerges through a sudden insight from fast-thinking is dramatically different from the kind of knowledge that accrues as a consequence of the disciplined, careful aggregation of data, information, and knowledge found through slow-thinking.

Below is an example of a complex design process — a score — designed for engaging with complex entanglements within complex environments. It’s complex. The stages and phases shown are just a part of a larger systems design process of courses that can be discussed at a later date.

The reason this particular score is shown here is to create the context for the fast-thinking example that follows, showing the point in the design score where sudden understanding emerges.

Complex liquid-crystal design ‘score’ / process

Emergent understanding at a particular point in a complex design score

ah-ha moment in fast-thinking

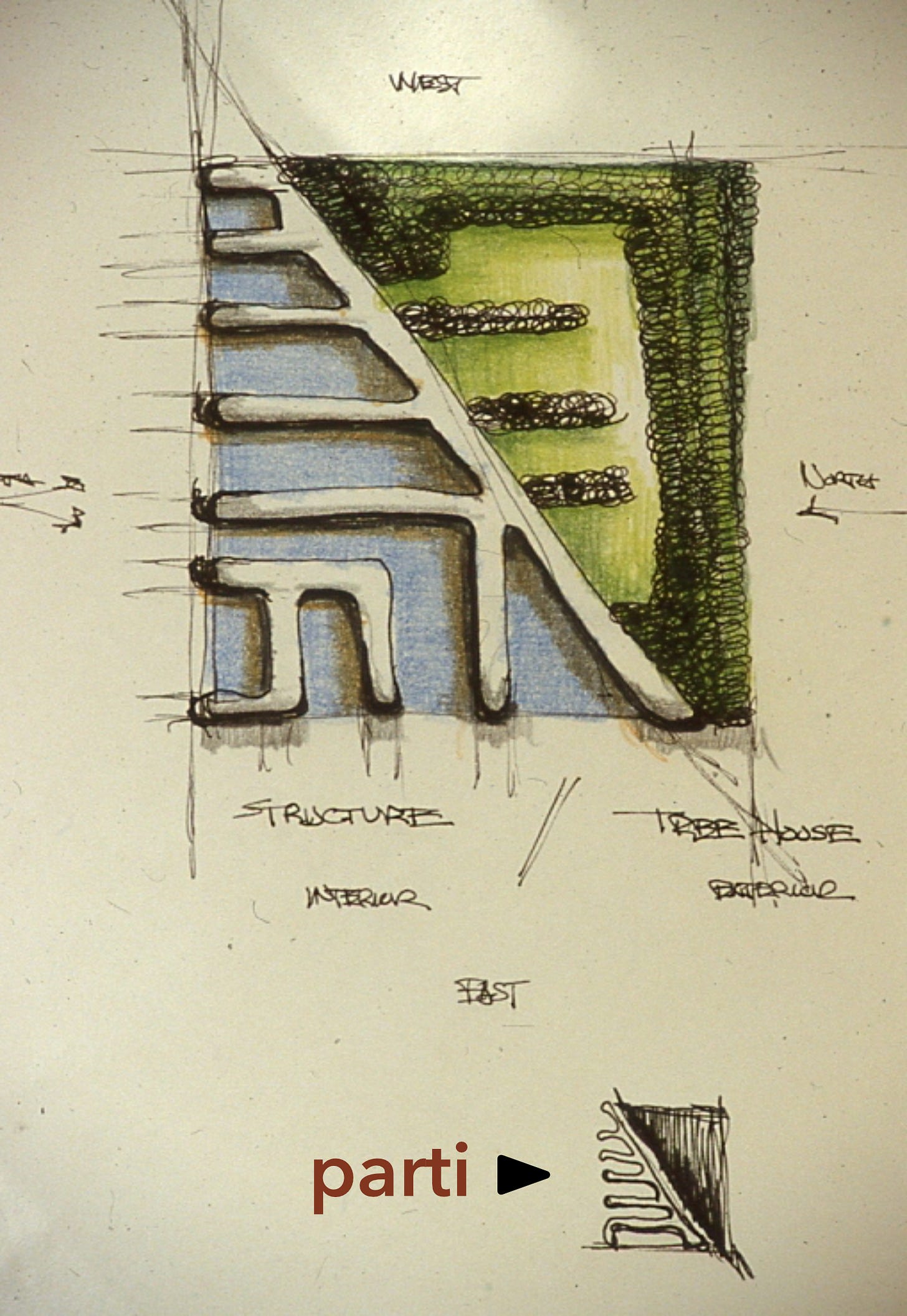

A typical ah-ha moment is a moment of emergent coherent understanding in the form of a unifying image. An example is the emergence of a ‘parti’ in architecture.

Ah-ha moment is a moment of sudden understanding or burst of insight. It results in an emergent unifying seminal image. The ah-ha insight is not the result of connecting elements and components into a functional assembly. It is not a composition.

ah-ha moment

example of an ah-ha as parti in architecture

A part is a seminal image of an abstract organizing system that unfolds through design inquiry into a more fully developed and mature complex design concept.

An example of an architectural parti and resulting influences

Looking outward - external focus

Many creative artists claim to be merely conduits for creative ideas from an outside, mysterious source. They disavow any involvement in fast-thinking themselves and are often uncomfortable looking more closely into the sources of fully developed creative insights from outside of themselves. Whatever the real nature of the mystery of externalized instant understanding is, it can be considered related to fast-thinking in principle and effect, even though it is firmly declared to be an external influence.

Sudden external inspiration is not a product of slow, deliberate analysis and careful critical assessment. Sudden inspiration gives order and meaning to complex, entangled challenges as if from a “bolt out of the blue” — a common expression. Sudden is sudden in relative terms.

Caravaggio: The Inspiration of Saint Matthew

Thoughts about thinking

Fast-thinking is an essential component of systemic inquiry. It is particularly important as an approach to inquiry for action followed by action. Slow-thinking is an essential approach to thinking for description, explanation, prediction, and control but fast-thinking is needed for intentional action.

Systemic design is a compound form of inquiry, including types of fast-thinking, slow-thinking, and synthetic-thinking. All these elemental approaches to inquiry that comprise systemic design inquiry are essential for dealing with complexity in human environments and contexts. Unfortunately slow-thinking dominates while fast-thinking is dismissed or glossed, and synthetic-thinking is mostly given lip service. This ought to be rethought and acted on.

Most importantly it is important to remember that fast-thinking is not instant gratification. Fast-thinking requires an investment of time, attention, and commitment.

Note: Graphics not generated by AI.

I want to propose that Design* as a way of bringing forth the unknown, is bastardized by the assumption that is just a creative way to solve problems. As Churchman said, problem solutions are found in the problem statement. Not so with Designs, because the outcome of a Design effort is a result of the intrinsic nature of the design process. And that Design effort is co-dependent upon the Designer(s).

And furthermore, the Design way defies the scientific method because it has no preconceived solution, and no way of predicting the outcome or the results thereof. The scientific way from the beginning cannot be the only approach to a novel solution because there can be no search for the truth of something that doesn't yet exist. That does not imply that the sciences are unimportant in the search for novelty and are inappropriate for designing. Quite the contrary, the sciences are importantly integrated into the Design process and usually vital to a desired outcome.

To that end, one of the Design functions, "Immersion," utilizes scientific knowledge found in the search for information, examples, case studies, research and analysis of associated issues of the Design effort. But as Dr. Nelson has pointed out, facts do not prescribe action, and Design is action that brings about change. It should be noticed that the Immersion stage of any design process is characterized by preparation based on known facts and ideas. But that is only the beginning, yet critical to knowing and understanding the initial conditions, from which the inquiry of "Divergence" can be launched and iteratively executed.

*NOTE: I capitalize the "D" to distinguish real Design as a complete process toward an output resultant from other assumptions.