systemic centaurs - part I

conjunctions of intensions and intentions

In Greek mythology, there is a ‘liminal being’ that represents the combined strengths of two different entities — horses and humans.

The centaur's half-human, half-horse composition has led many writers to treat them as liminal beings, caught between the two natures they embody in contrasting myths; they are both the embodiment of untamed nature, as in their battle with the Lapiths (their kin), and conversely, teachers like Chiron.

Wikipedia (retrieved July 2025)

lame gods and prosthetic gods

Humans, as hosts for technology, are ‘prosthetic gods’. ‘Prosthetic gods’ are a form of ‘liminal being’ like centaurs. Humans do not want to settle for natural competencies. They want to be ‘unnatural’, with greater abilities and capabilities than are granted to them naturally. They want to be integrated or unified with their favored technologies:

Man has, as it were, become a kind of prosthetic God. When he puts on all his auxiliary organs he is truly magnificent; but those organs have not grown on to him and they still give him much trouble at times.

—Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (1930)

Technology is an unnatural addition to natural human abilities. The combination of technology and natural abilities is fraught with danger but has also been beneficial. There is an ongoing struggle to determine what form of technology should be brought into existence and how it should be innovated into the lives of others. This is a continuing challenge for good designers who are, in essence, ‘lame gods’ — with unlimited potential but with limited knowledge and understanding. Lame gods stand in the service of ‘prosthetic gods’ — a demanding responsibility.

Human agents, as lame gods, are archetypal designers. Hephaistos, an archaic mythic god of forge and fire from Greek mythology, is a prototype designer and craftsman. Hephaestus, unlike the other more perfect gods, had limited physical abilities but unlimited creative potential. The other, more perfect gods were clever and cunning but not necessarily creative.

Because of his condition, he created technologies like golden robots and winged chariots to help him compensate for his limitations. Because of his success with his creations, he was asked to create armor, weapons, jewelry, homes, and other desirable things for the other uncompromised gods after they had admiringly witnessed and admired what he could do.

technologies and human agency

New technologies in general, such as personal computers, and more recently the emergence of so-called artificial intelligence (AI), have become, or are becoming, prosthetics fitted to modern humans. But how well do these new prosthetics fit human nature?

The discussions in response to this question have so far been polarizing. The noise levels promoting AI technologies are aggressive and loud as well. Those who stand to gain the most economically from this new form of technology are extolling AI while debasing human competencies and abilities — humans need AI because they are inferior and weak without it.

Humans have acknowledged the limitations of their abilities, certainly. But the cults of human debasement have been around for a long time and have been influential in promoting alternatives to human agency, creating a need for human husbandry. The rhetoric has been meant to degrade and gaslight humans while extoling the virtues of technology in order to persuade humans to give over on their natural strengths and the rights to agency in their lives.

How can these narratives be turned towards finding appropriate relationships between the creators of technology and their intended consumers? How can the creators of technology be encouraged to serve the best interests of their customers? How is the case made for creating appropriate relationships with the powerful technologies that continue to arise regularly?

For example, many who are cautious and concerned about AI are left to champion the fundamental abilities and competencies of human beings, in their own right. The prudent do not reject AI technologies out of hand, but they want the technologies to be carefully designed and evaluated with an eye towards human fit and benefit. They desire appropriate instrumental subsystems formed into teleological social systems, such as organizations, including governmental, business, etc., created to serve their best interests.

The question is, how to do this? How to create appropriately designed modern centaurs integrating human agency and high-speed computer data manipulation. Such centaurs are a good fit in some human activities, but not in all. For systemic designers, the question is how to design teleological social systems composed of subsystems formed at the conjunction of human aims and outcomes — effective systems created for the right reasons, at the right time, for the right people in the right place.

For those operating teleological social systems — leaders, executives, managers, and administrators — the question is how they can make the right use of the degrees of freedom they have access to in the operation of the system.

The conjunctions of humans and their technology — prosthetic gods — require an integrative fitting process based on careful discernment and competence. It is a much more challenging process than one is led to believe, listening to vendors and promoters of the AI technologies. The processes of integration are complicated and complex, but necessary for real and lasting success.

To assist in the challenge of framing and forming these conjunctions, there needs to be a clear understanding of what technology is in general and what AI is in particular, as related to securing improvement in the human condition.

For example, AI technologies are not surrogate life forms as implied by the language used to describe them. The words imply human qualities — i.e., anthropomorphism. In this form of animism, terminology used to describe AI technology implies that AI is intelligent, it learns, hallucinates, and is conscious, etc. This is extremely misleading and tends to create more anxiety and animosity towards the technology. (https://hnelson.substack.com/p/stop-scaring-people)

necessity of free will and design freedoms

Designing and operating systems that are conjunctions of human agency and computer technologies requires certain degrees of freedom for inquiry, learning, and taking action — both in creating and operating systems. Degrees of design freedom are based on the existence of free will:

design freedoms

The following descriptions are an example of a schema for lame gods in the service of prosthetic gods to design and manage teleological social systems in conjunction with technologies related to or including artificial intelligence (AI). It is just one example, but it is a useful one demonstrating the complexity of creating and using ‘centaur’ systems in guiding or assisting human behavior to navigate complex realities.

Designing and operating complex social systems composed of conjunctions between human agency and computer technologies — centaurs — include both particular means and concomitant methods. The choice of approach — designing, planning, problem solving, etc. — will determine the choices of forms and content of individual actions or activities.

The actions involved include:

• designing systems to have degrees of freedom for inquiry, for action, and for taking action.

• operating systems using requisite levels of freedom for action.

The activities involved include:

• describing and explaining subsystems and systems

• predicting and controlling subsystems and systems

Designing — systemic designing— is primarily learning. A design activity is a learning process. A systemic design process is a learning process preparing for action. Designers must have the necessary capacity for learning and the necessary degrees of freedom to learn at the right levels of engagement. The challenge is to design concomitant learning systems with the requisite degrees of freedom for learning and for action at the right levels.

activity cells and action spaces

Cases made for ideal organizational templates abound. There are a variety of popular solutions that are put forward, such as flat, hierarchical, matrix, or modular systems, etc. But in reality, there is no one ideal design for any social system, including organizational systems. Systemic design and operation create or animate particular systems for particular situations and purposes.

Organizational systems or subsystems must be designed and managed to fit their purpose and agents. Their design needs to be guided by performance and prescriptive specifications. For instrumental purposes, they need to embody the capacity, competence, and abilities required to carry out their intentsions and intentions.

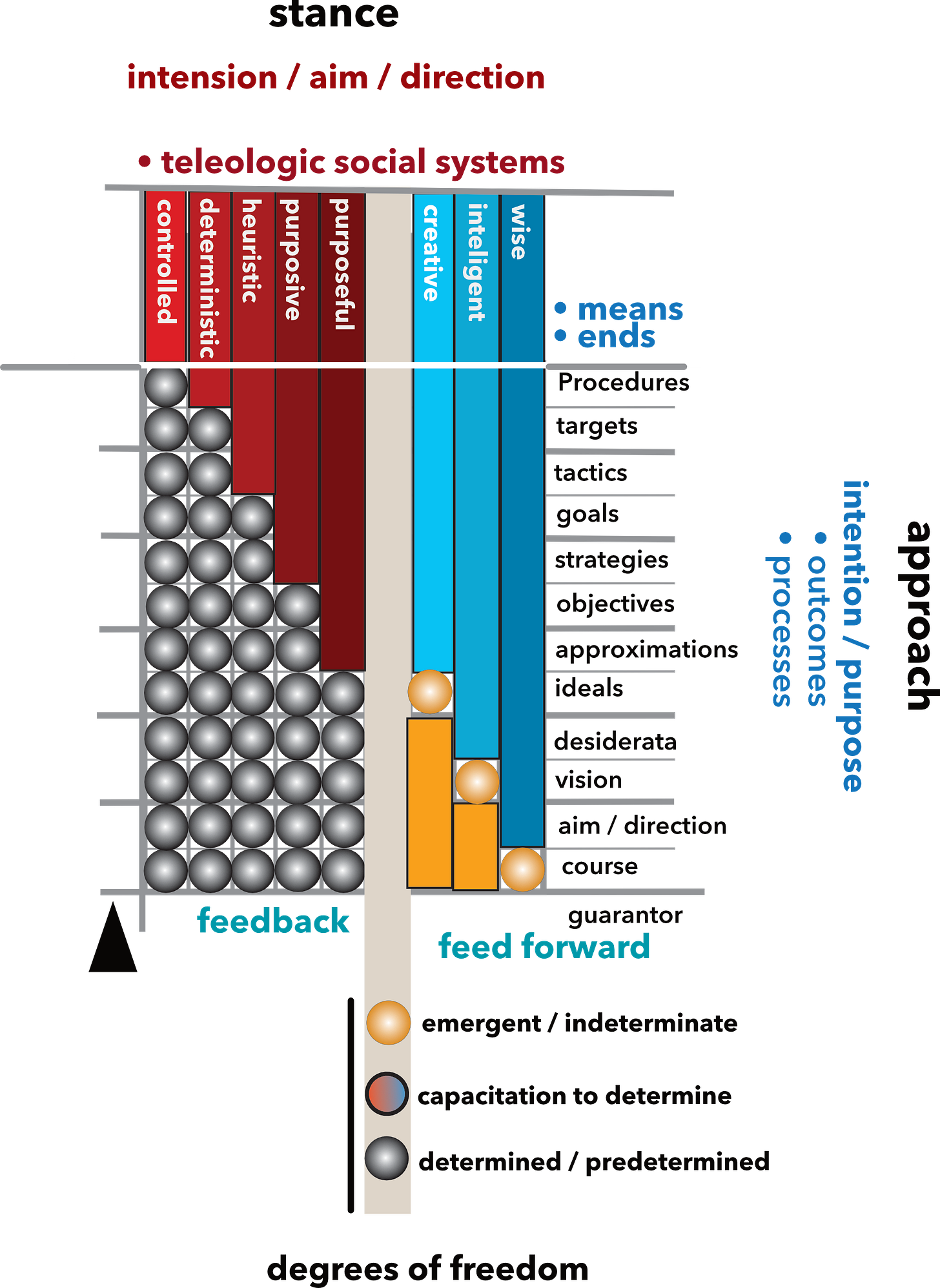

Teleological social systems, like organizations, are designed and operated by a synthesis of ‘intension’ (direction) and ‘intention’ (outcome). Different kinds of social systems require access to multiple degrees of freedom, inquiry, and action for the creation of functional subsystems making up individual teleologic systems.

Multiple degrees of freedom for engaging in inquiry and action within functional subsystems are necessary for the specific teleologic systems to accomplish their designed teleologic outcomes. The breadth of free will of functional subsystems is defined by a palette of freedoms they have designed into them. The particular level of freedom is determined by both ‘stance’ and ‘approach’ and includes:

Intension — stance

teleologic form

• controlled

• deterministic

• heuristic

• purposive

• purposeful

• creative

• intelligent

• prudent

• wise

Intention — approach

ways, means & ends

• procedures / methods / tools

• targets

• tactics

• goals

• objectives

• approximations

• ideals

• aspirations / outcomes

• intentions / purpose

• direction

• intensions / aim

designers and operators

Designing or operating the right kind of system for particular situations is not a simple, straightforward activity. No panaceas match the challenge. But two approaches are available, depending on the desired outcome.

The first approach is that of the foundational creators or designers. The second approach is that of system operators within an established system. The two activities are distinguished from each other in that the activity of designing or creating particular systems is done from an external agency role outside of the system under assembly — meta roles in essence. The internal activities of leading, managing, administering, or staffing systems are from inside positions — participant roles.

Below is the schema of a teleological social system matrix showing the conjunction spaces between stances and approaches to learning or action. In the version shown, different colors identify distinct types of social systems and the areas of intention that are open to the interactive determination of means and outcomes.

stance and approach matrix

The matrix shows the form and structure of particular types of teleological social systems based on the degrees of freedom to make inquiry or to take action within each of their conjunction spaces or cells. The identification of the type of system being looked at is determined by the open or closed predisposition of each particular conjunction cell. Each teleological social system is identified by a profile showing the degrees of freedom within each conjunction cell that are either determined or indeterminate. Each conjunction cell specifies the required abilities, competencies, and capacities of the human agents to make their determinations for indeterminate states-of-affairs.

The challenge, of course, is that people seldom understand clearly what and why they do the things they do in the way they do them when they are operating or creating social systems. That makes it difficult, for instance, to determine where or if AI technologies should fit into their processes and how the technologies should be utilized, if at all, which means there is an equal need to understand the nature of the technologies

In this case, a matrix like this helps show the characteristics and qualities of the influences of intentions and intentions on one another. This helps to reduce the complexity of grasping a holistic overview a bit.

This schema of a matrix is not a complicated graphic, but it is complex. It requires time and attention to understand it more fully. As complicated as the matrix may appear, it is nevertheless useful and necessary when dealing with complex and powerful technologies like AI in complex contexts and environments. This matrix is merely an overview in preparation for developing specifics in gaining a greater understanding by means of a more thorough process of assessment.

The individual teleologic systems do not share contexts or environments necessarily, so each type can be approached and dealt with on its own in its place as needed and appropriate. The selection of the particular system type depends on the judgments of agents outside of the matrix’s functional framework to match their aim and outcome needs, as well as the needs of those inside the framework.

A deep understanding of how to bring these teleological social systems into existence and how to operate them is required when evaluating how to integrate complex technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) as either an augmentation to, or replacement for, human agency. There needs to be a discernment of which activities best fit the strengths of AI and which are best left to people using AI as a functional tool, or when people do better on their own. There is a need to understand where, how, and if AI supports human strengths in the processes of each functional subsystem.

For example, what is involved in the design or implementation of ‘strategies’ in the pursuit of ‘objectives’ as shown in the matrix? Good answers are challenging and require careful consideration. Finally, there is a need to understand where AI is not a good fit or relevant to the learning and actions occurring in certain functional subsystems and why any efforts to force AI onto the processes are counterproductive and unhelpful.

conjunctions in the systemic design matrix

Two basic types of conjunctions determine the kind of inquiry or action that can be taken.

types of conjunction cells

There are two general categories of constituents within subsystem conjunctions — action and form.

cellular categories of freedom

Part II — exploring the inclusion of AI in social systems

In Part II of this series, the first steps in integrating or infusing AI technology into functional subsystems or assemblies will be explored in more detail. Part II deals with the challenge of attaching AI as a prosthetic technology onto a host operational subsystem in a teleological system. It is more of a roadmap than a destination.