systemic pedagogy

interactions and fit for systemic learning

Russ Ackoff on systems analysis and synthesis

Russ’s insights on synthesis and analysis are missed even by many systems practitioners. His insight into the systemic nature of automobiles and architecture as complex functioning assemblies focuses on how things fit together. There are no general or universal automobile designs, just as there are no general or ideal building designs. There are particular designs for particular situations. This holds for organizational systems as well, including business, education, health, transportation, and government.

Ideally, organizational systems are assembled from components or elements that are designed to fit together into functional wholes. The consequence is that when designing systems, the elements and components are formed or chosen based on their fit with the other components or elements that share a common overall purpose. Their inclusion in the system is based on their collective contributions to the system's emergent character and essential quality. This is true for activities as well, such as in the case of education, which will be discussed later.

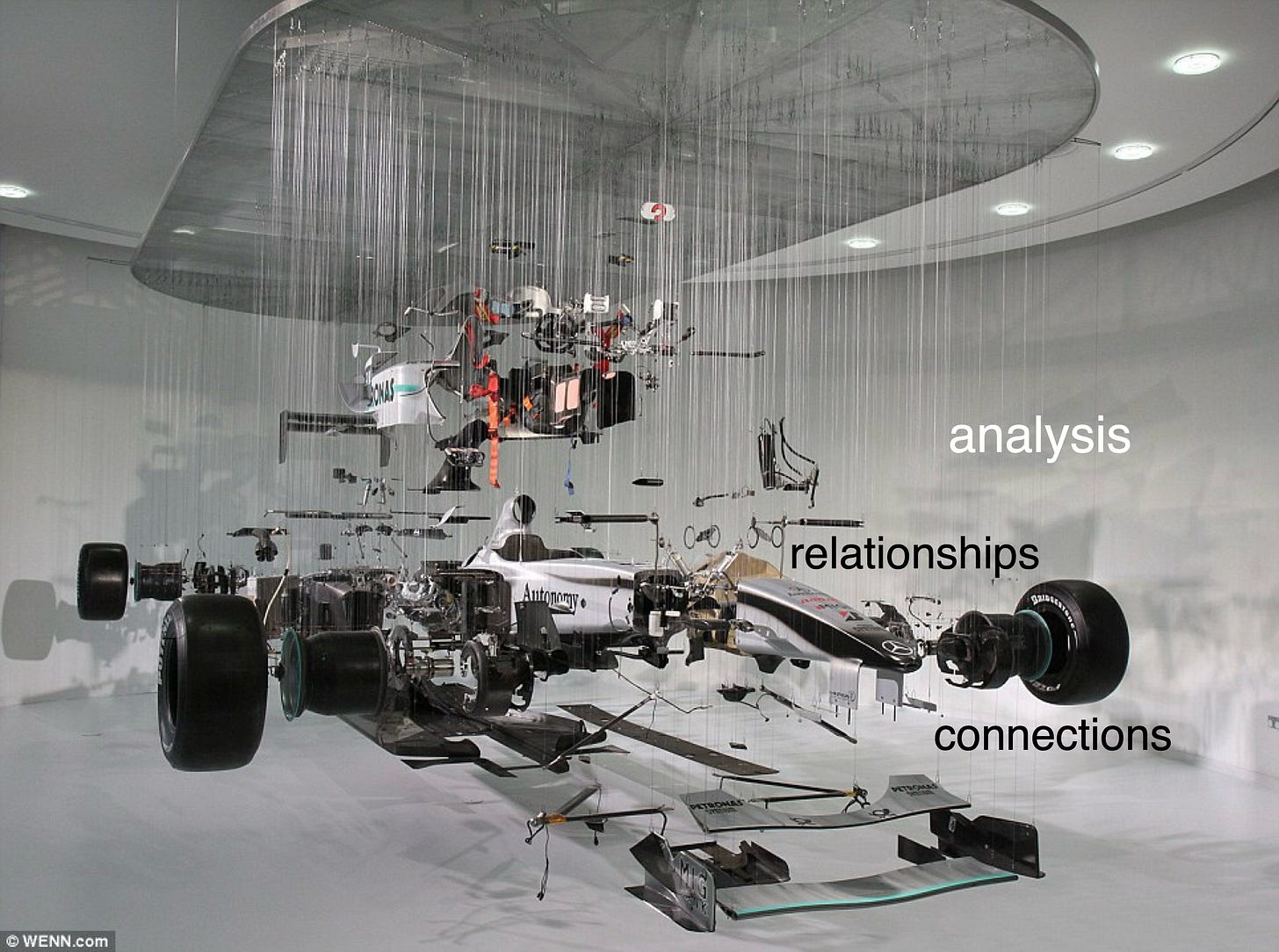

The image of an automobile shown below — a high-performance racing car — shows the components of the car and their relationship with each other, but does not show the fit or connection between the individual elements, which are fundamental to the car’s functional integrity. Systems practitioners are typically good at describing the parts and explaining the interrelationships of systems or states. But as Ackoff explains, it is the connections between the parts that are important to understand.

disassembled racing car

Ackoff’s automobile and architecture analogy approaches

Expanding on Russ Ackoff’s car and architecture analogy, there are at least seven approaches to consider:

Evaluating existing systems and states

1 describing

2 explaining

3 analyzing

4 assessing

Designing systems and states

5 determining what is desirable

6 making

7 using

analysis and synthesis

analyzed assembly

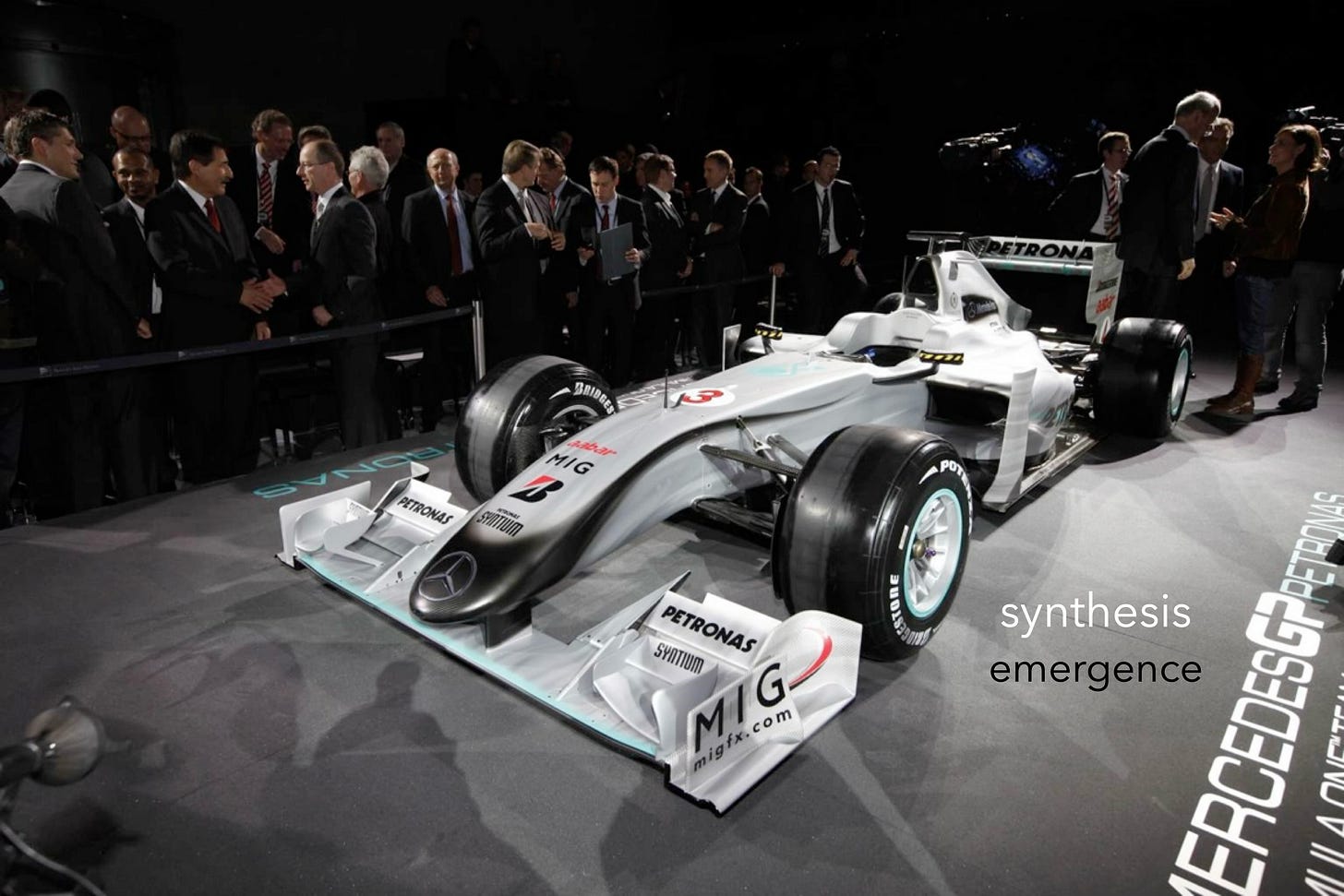

assembled automobile

automobile in context and environment

determining what a desirable system or state would be

As a systemic designer, it is important to be able to determine not only what elements need to be part of the system — ‘analysis’, but what relationships and connections need to be put into place as well — ‘synthesis’. So, how does a potential systemic designer learn to do this? Even more importantly, how do they learn how to determine what a desirable system or state-of-affairs would be in a particular instance? This is not a central concern for systems practitioners who primarily operate, maintain, or repair systems or manage states, but it is absolutely central to those who design them.

designing systemic learning systems based on Ackoff’s insights

‘Learning systems’ are designed around a variety of pedagogies, traditionally, as seen in schools of different kinds, from grade schools to universities. But for systemic designing, the pedagogy is distinct in that it reflects the principles of assembly shown in the analogy of automobiles and architecture that Russ Ackoff talked about. The classes or learning experiences — elements — need to be related and connected in such a way as to support the individual’s learning as a whole.

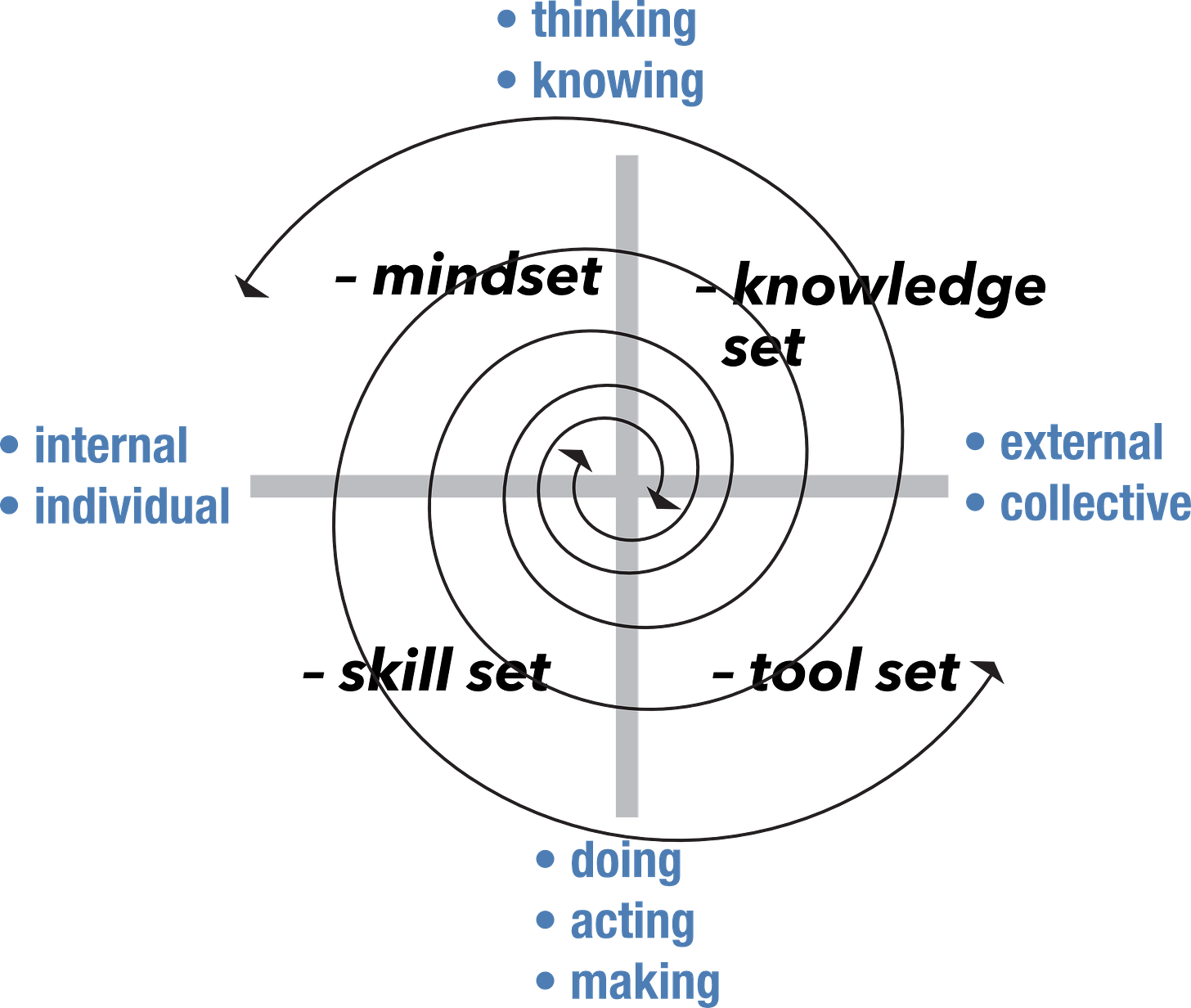

sets

It is quite common to see independent learning activities like ‘courses’ offered as independent, stand-alone offerings. They are advertised as transferable and applicable to practice in general. This may hold for courses that are primarily transferals of what is true or known. But they are just contributing to ‘knowledge sets’, which is insufficient. Foundational ‘mindsets’ are unique to each learner and are coherent compositions of learning experiences that need to be developed fully (see below).

sets

Stand-alone courses or other learning events are often touted as exemplary of one of the ‘best’ of their kind. Russ Ackoff’s video presentation linked above is a reminder of why you can’t have an assembly of ‘best’ learning experiences that is functional, let alone ‘best’ design, unless the individual learning events have been designed to relate, connect, link, or bond with one another, resulting in an emergent, congruent, holistic educational experience for the learner. The courses become just contributions to skill sets and tool sets rather than contributing elements or components to an integrated learning experience.

Pedagogical approaches to learning to engage in synthesis as well as analysis require that separate learning experiences be interrelated and fit together to contribute to a desired learning as a whole.

Nowadays, university programs often offer a ‘capstone experience’ that purports to pull the individual learning experiences of students into a coherent whole. As Russ Ackoff reminds us with his car and architecture analogy, putting individual elements — even ‘best of class’ — together will not result in a congruent whole. For programs without ‘capstone courses’, the students are left on their own to integrate and synthesize their learning into an integrated whole.

Educational pedagogies for systemic design learning need to be framed and formed systemically using Ackoff’s insights.