Shuhari

Aikido master Endō Seishirō shihan stated:

"It is known that, when we learn or train in something, we pass through the stages of

shu, ha, and ri. These stages are explained as follows. In shu, we repeat the forms and

discipline ourselves so that our bodies absorb the forms that our forebears created. We

remain faithful to these forms with no deviation. Next, in the stage of ha, once we have

disciplined ourselves to acquire the forms and movements, we make innovations. In

this process, the forms may be broken and discarded. Finally, in ri, we completely

depart from the forms, open the door to creative technique, and arrive in a place where

we act in accordance with what our heart/mind desires, unhindered while not

overstepping laws."

Shuhari (Kanji: 守破離 Hiragana: しゅはり) is an evolving Japanese martial art concept that describes the stages of learning leading to mastery. It has also been applied to other domains, disciplines, or traditions of inquiry and learning.

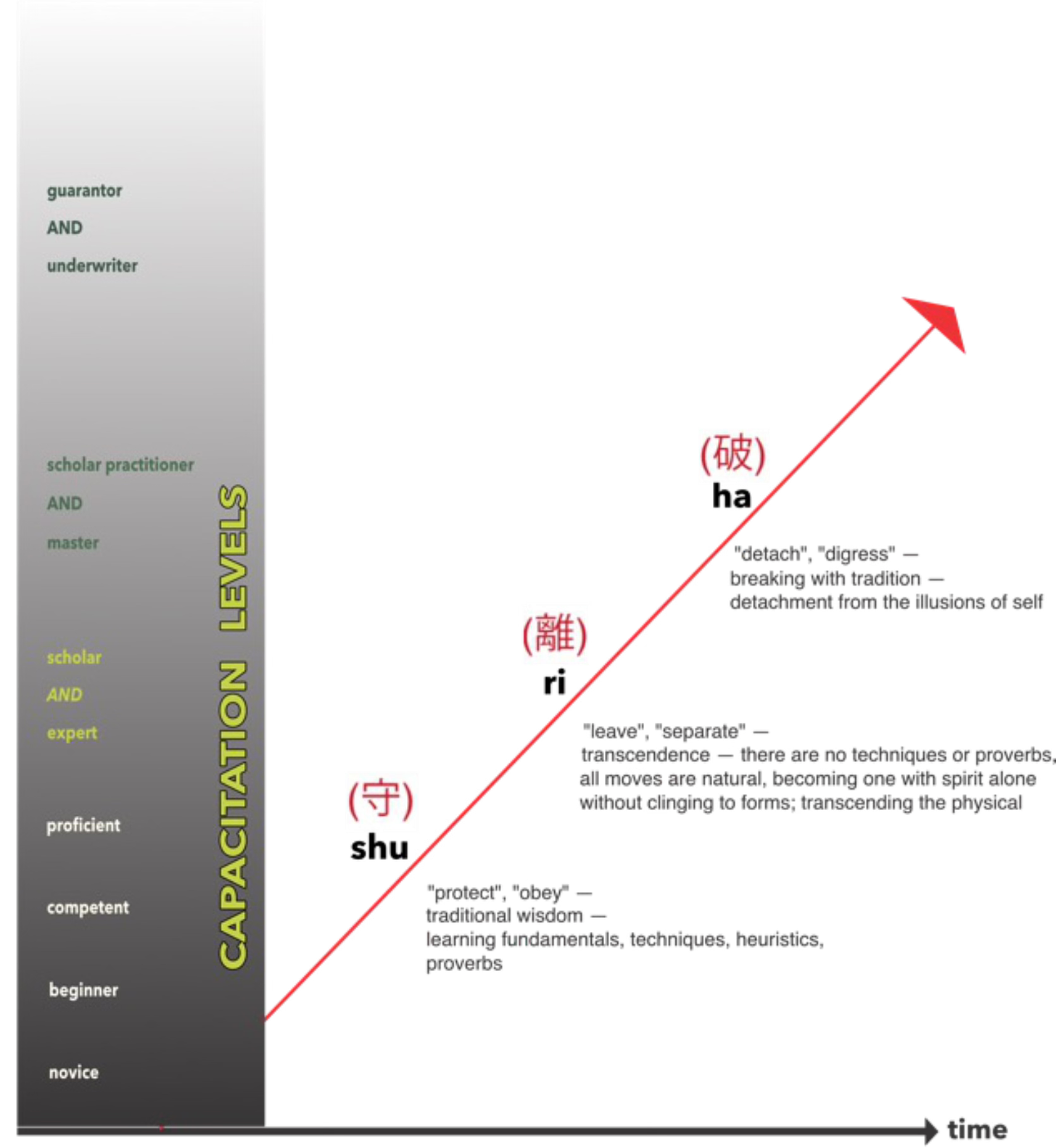

Shuhari can be disaggregated into phases of learning:

shu (守) "protect", "obey"—traditional wisdom—learning fundamentals, techniques, heuristics, proverbs.

ha (破) "detach", "digress"—breaking with tradition—detachment from the illusions of self, to break with tradition - to find exceptions to traditional wisdom, to find new approaches.

ri (離) "leave", "separate"—transcendence—there are no techniques or proverbs, all moves are natural, becoming one with spirit alone without clinging to forms; transcending the physical - there is no traditional technique or wisdom, all movements are allowed.

Gaining mastery of abilities and skills over a lifetime of learning marks a progress from instrumental or intentional learning through creative learning to intensional learning as exemplified in the tradition of Shuhari (shu – ha – ri) which is found in a variety of expressions ranging from traditional Japanese martial arts to formal tea ceremonies. This pattern has influenced or informed many approaches to learning and training in other cultures over the centuries. Similar approaches have often evolved naturally on their own yet share a similar pattern of accomplishment in learning.

The following is an example of a designed approach to learning to become a systemic designer. This example also applies to the development of other learning strategies in other professional domains.

Marking progress when learning to become a systemic designer.

Grades, certificates, and degrees are the usual way that progress in learning is marked in formal education with progress based on tests and evaluations. In informal education, experience is used as a marker of progress through various demonstrations of competence.

Stone masons building gothic cathedrals formally marked their progression in learning using a parallel path. One path marked the mastery of different kinds of tools. At the same time, each tool was matched to a quality of character. Questions like “Are you being on the level with me?” or “Are you being square with me?”, were questions of character as analogies of a tool’s purpose — ‘levels’ and ‘squares’ in this case.

Below is an example of a ‘smooth’ transition or ‘flow’ scale, which is not based on discrete levels or steps. The scale indicates stratums of attainment in becoming a systemic designer that flow into one another. Such learning occurs in both formal and informal learning contexts. It is defined as learning to design for action rather than just learning to describe and explain things.

Below is an example of an integration of Shuhari and a professional systemic designer’s capacitation. Experience — time — forms the horizontal axis.

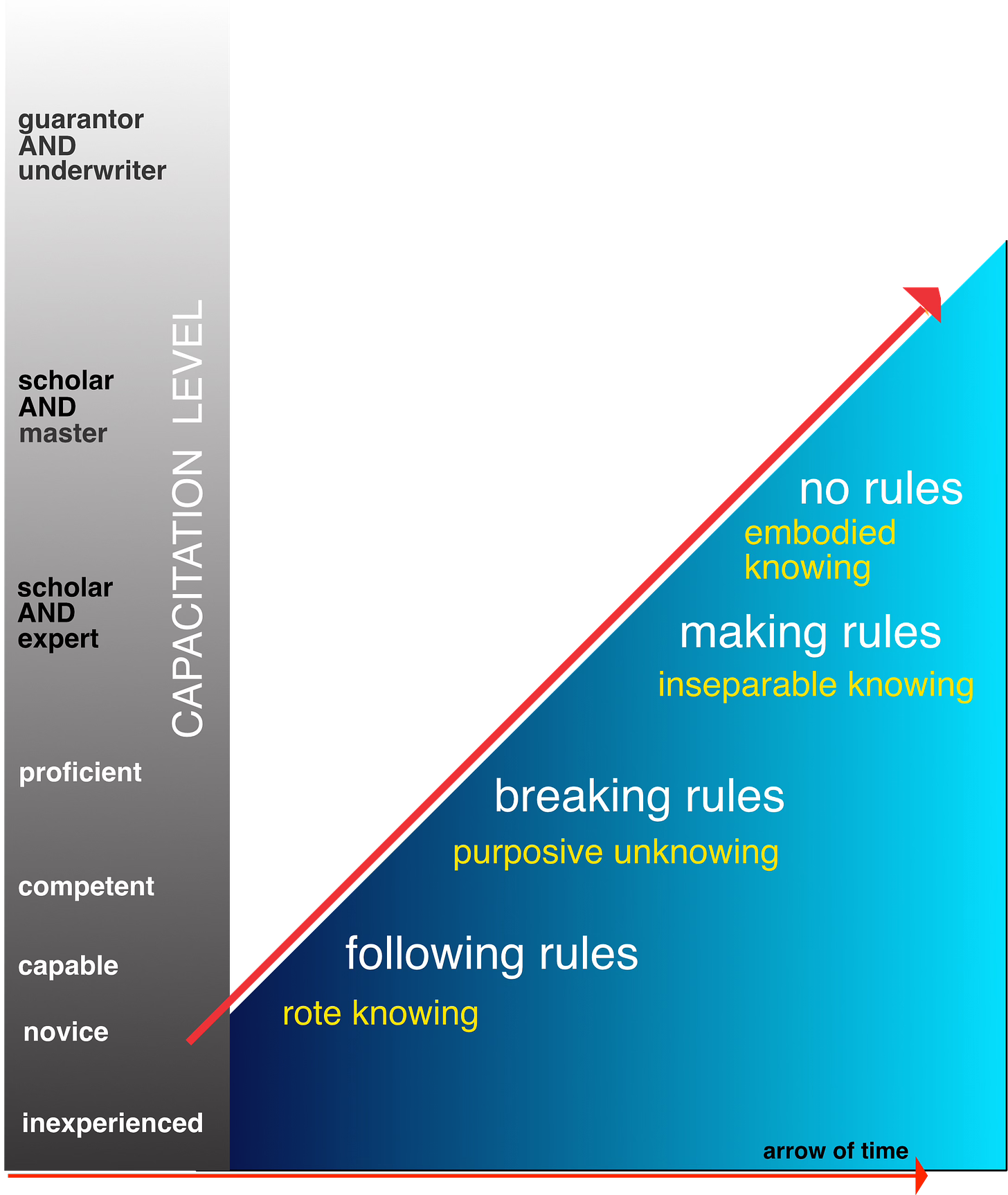

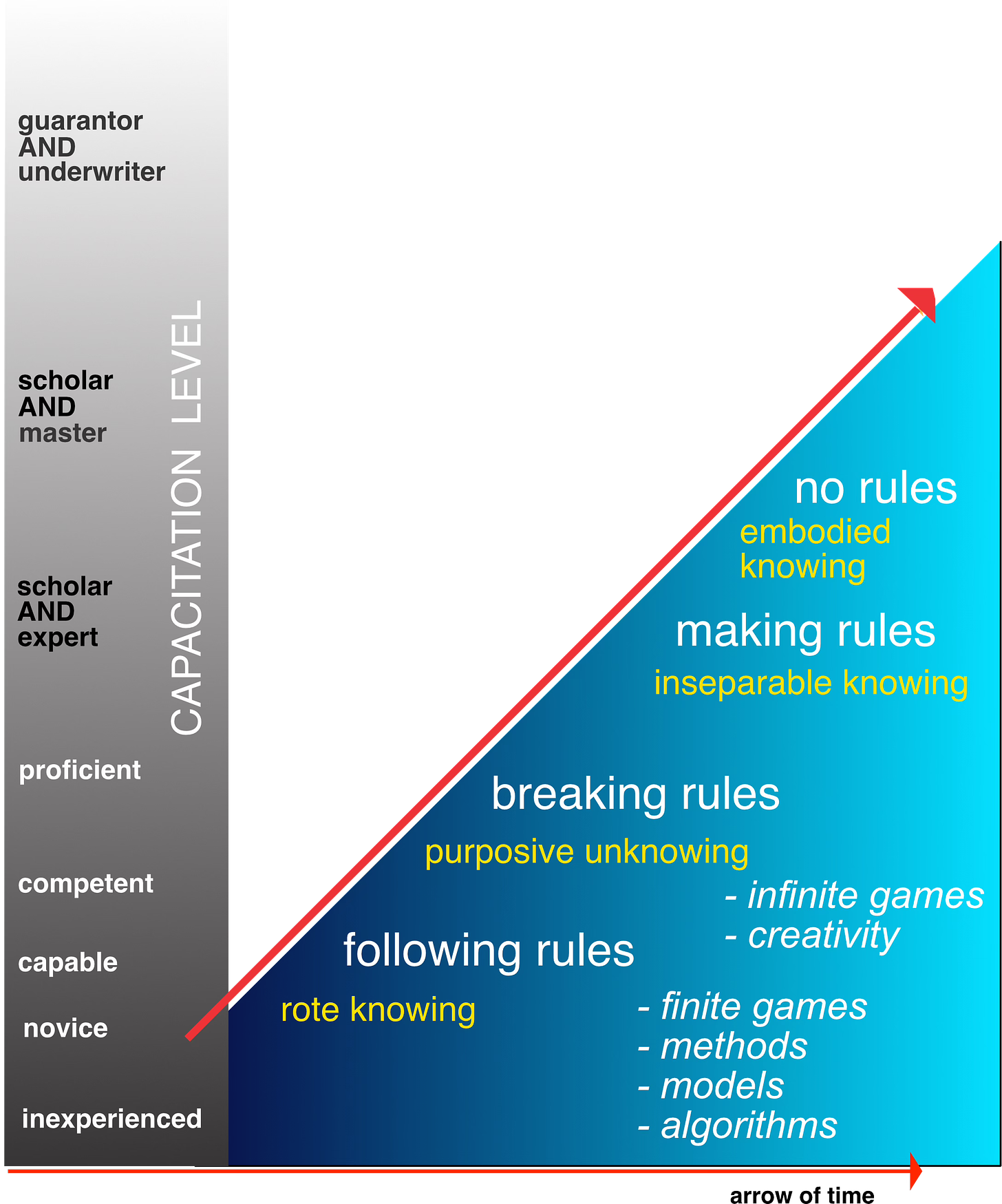

Below is a Western adaption and expansion of a Shuriha process focused on ‘rules’. The focus on rules is just one of many possibilities.

The normative focus shown below is on methods, models, and algorithms as elements or components of ‘finite games’ (Carse, James, Finite and Infinite Games: http://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Finite-and-Infinite-Games/James-Carse/9781476731711) — concerning following ‘rules’. Training dominates this stratum and it is the area that most academic, business, and governmental organizations focus time and resources on. Learning dominates the next strata.

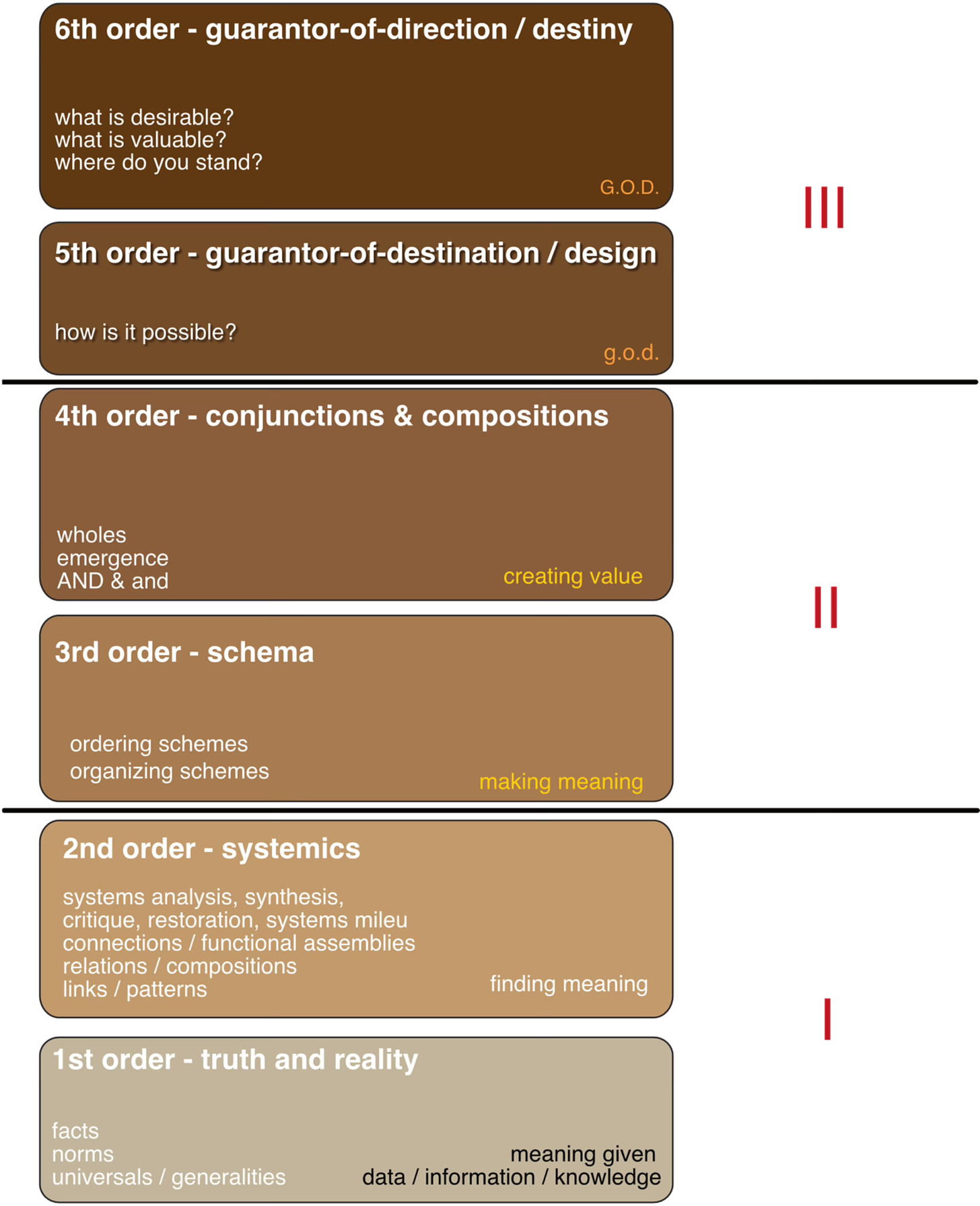

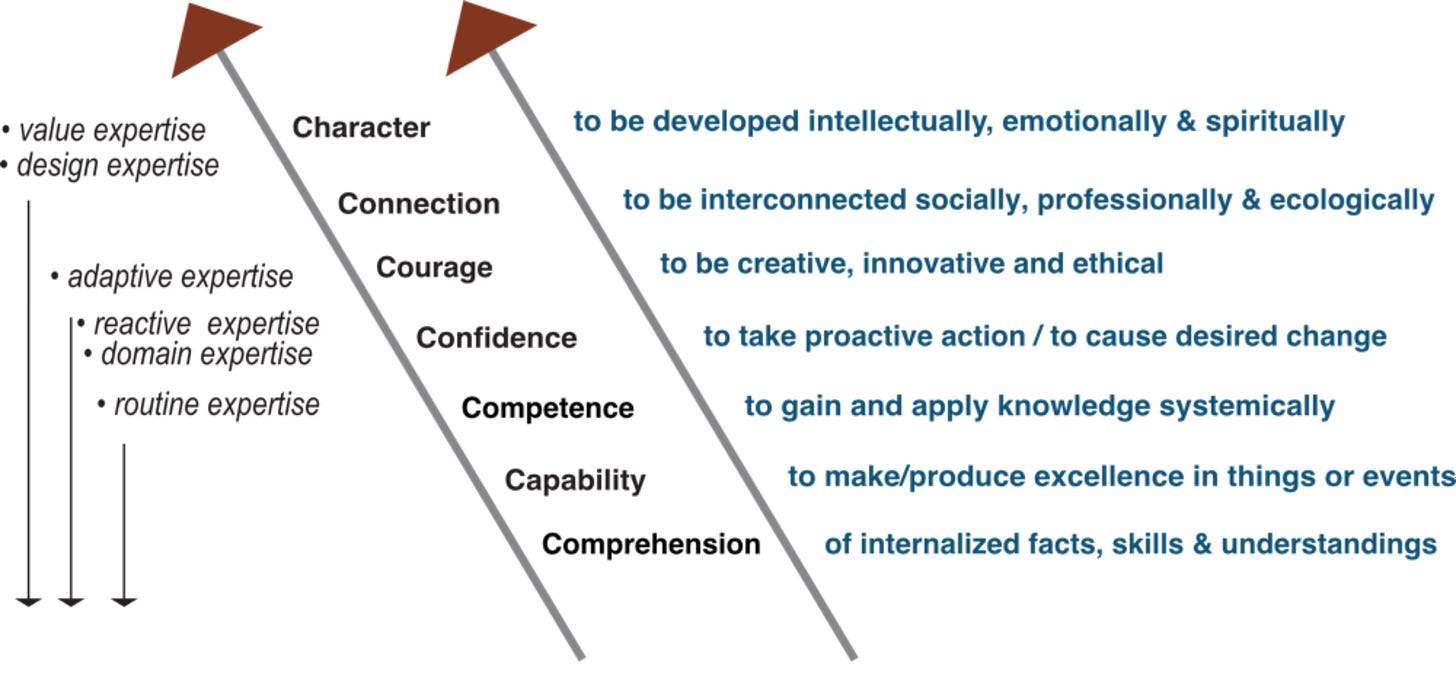

The Shuhari-influenced framework is just one example of the many ways to comprehend systemic design learning — learning in preparation for intensional action and for taking intentional action. The two illustrations below are from other systemic perspectives. The illustrations require a great deal more explanation of course but are offered here primarily as exemplars to give a sense of the diversity of stances and approaches to fleshing out the nature of learning. They are complex as expected but have value for real-world situations because of that.

domains of learning and training

A multilevel example —shown below — is of a structural approach to identifying competency levels. It implies a necessary transition-focused process moving from lower levels to higher levels of understanding and competency as desired. The different domains, or stratums, require different approaches to learning. In addition, it implies the necessity of learning how to facilitate transitions from lower stratums to a higher one — ie facilitating an arrow of time.

Capacitation Levels for Systemic Design Learning and Training

Unlike picking a domain for focused attention, a higher level of a hierarchy requires that lower levels are determined to some degree. Higher levels depend on some groundwork being established and boundaries set.

Levels of Expertise are Dependent on Mastery of Hierarchic Foundational Abilities

Learning is not just about becoming a designer. It is the fundamental activity of a designer designing. It is a complex and demanding activity but looking at the work of any accomplished professional in any domain of practice these activities are essential to the application of learning and experience to real-world projects.